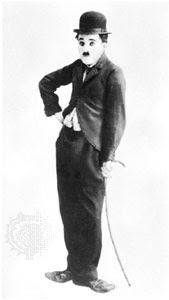

Charlie Chaplin is the endearing figure of his Little Tramp was instantly recognizable around the globe and brought laughter to millions. Still is. Still does Every few weeks, outside the movie theater in virtually any American town in the late 1910s, stood the life-size cardboard figure of a small tramp – outfitted in tattered, baggy pants, a cutaway coat and vest, impossibly large, worn-out shoes and a battered derby hat – bearing the inscription I AM HERE TODAY. An advertisement for a Charlie Chaplin film was a promise of happiness, of that precious, almost shocking moment when art delivers what life cannot, when experience and delight become synonymous, and our investments yield the fabulous, unmerited bonanza we never get past expecting.

Eighty years later, Chaplin is still here. In a 1995 worldwide survey of film critics, Chaplin was voted the greatest actor in movie history. He was the first, and to date the last, person to control every aspect of the filmmaking process – founding his own studio, United Artists, with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith, and producing, casting, directing, writing, scoring and editing the movies he starred in. In the first decades of the 20th century, when weekly moviegoing was a national habit, Chaplin more or less invented global recognizability and helped turn an industry into an art. In 1916, his third year in films, his salary of $10,000 a week made him the highest-paid actor – possibly the highest paid person – in the world. By 1920, “Chaplinitis,” accompanied by a flood of Chaplin dances, songs, dolls, comic books and cocktails, was rampant. Filmmaker Mack Sennett thought him “just the greatest artist who ever lived.” Other early admirers included George Bernard Shaw, Marcel Proust and Sigmund Freud. In 1923 Hart Crane, who wrote a poem about Chaplin, said his pantomime “represents the futile gesture of the poet today.” Later, in the 1950s, Chaplin was one of the icons of the Beat Generation. Jack Kerouac went on the road because he too wanted to be a hobo. From 1981 to 1987, IBM used the Tramp as the logo to advertise its venture into personal computers.

Born in London in 1889, Chaplin spent his childhood in shabby furnished rooms, state poorhouses and an orphanage. He was never sure who his real father was; his mother’s husband Charles Chaplin, a singer, deserted the family early and died of alcoholism in 1901. His mother Hannah, a small-time actress, was in and out of mental hospitals. Though he pursued learning passionately in later years, young Charlie left school at 10 to work as a mime and roustabout on the British vaudeville circuit. The poverty of his early years inspired the Tramp’s trademark costume, a creative travesty of formal dinner dress suggesting the authoritative adult reimagined by a clear-eyed child, the guilty class reinvented in the image of the innocent one. His “little fellow” was the expression of a wildly sentimental, deeply felt allegiance to rags over riches by the star of the century’s most conspicuous Horatio Alger scenario.

From the start, his extraordinary athleticism, expressive grace, impeccable timing, endless inventiveness and genius for hard work set Chaplin apart. In 1910 he made his first trip to America, with Fred Karno’s Speechless Comedians. In 1913 he joined Sennett’s Keystone Studios in New York City. Although his first film, Making a Living (1914), brought him nationwide praise, he was unhappy with the slapstick speed, cop chases and bathing-beauty escapades that were Sennett’s specialty. The advent of movies in the late 1890s had brought full visibility to the human personality, to the corporeal self that print, the dominant medium before film, could only describe and abstract. In a Sennett comedy, speechlessness raised itself to a racket, but Chaplin instinctively understood that visibility needs leisure as well as silence to work its most intimate magic.

The actor, not the camera, did the acting in his films. Never a formal innovator, Chaplin found his persona and plot early and never totally abandoned them. For 13 years, he resisted talking pictures, launched with The Jazz Singer in 1927. Even then, the talkies he made, among them the masterpieces The Great Dictator (1940), Monsieur Verdoux (1947) and Limelight (1952), were daringly far-flung variations on his greatest silent films, The Kid (1921), The Gold Rush (1925), The Circus (1928) and City Lights (1931).

The terrifyingly comic Adenoid Hynkel (a takeoff on Hitler), whom Chaplin played in The Great Dictator, or M. Verdoux, the sardonic mass murderer of middle-aged women, may seem drastic departures from the “little fellow,” but the Tramp is always ambivalent and many-sided. Funniest when he is most afraid, mincing and smirking as he attempts to placate those immune to pacification, constantly susceptible to reprogramming by nearby bodies or machines, skidding around a corner or sliding seamlessly from a pat to a shove while desire and doubt chase each other across his face, the Tramp is never unself-conscious, never free of calculation, never anything but a hard-pressed if often divinely lighthearted member of an endangered species, entitled to any means of defense he can devise. Faced with a frequently malign universe, he can never quite bring himself to choose between his pleasure in the improvisatory shifts of strategic retreat and his impulse to love some creature palpably weaker and more threatened than himself.

When a character in Monsieur Verdoux remarks that if the unborn knew of the approach of life, they would dread it as much as the living do death, Chaplin was simply spelling out what we’ve known all along. The Tramp, it seemed, was mute not by necessity but by choice. He’d tried to protect us from his thoughts, but if the times insisted that he tell what he saw as well as what he was, he could only reveal that the innocent chaos of comedy depends on a mania for control, that the cruelest of ironies attend the most heartfelt invocations of pathos. Speech is the language of hatred as silence is that of love.

On Chaplin’s first night in New York in September 1910, he walked around the theater district, dazzled by its lights and movement. “This is it!” he told himself. “This is where I belong!” Yet he never became a U.S. citizen. An internationalist by temperament and fame, he considered patriotism “the greatest insanity that the world has ever suffered.” As the Depression gave way to World War II and the cold war, the increasingly politicized message of his films, his expressed sympathies with pacifists, communists and Soviet supporters, became suspect. It didn’t help that Chaplin, a bafflingly complex and private man, had a weakness for young girls. His first two wives were 16 when he married them; his last, Oona O’Neill, daughter of Eugene O’Neill, was 18. In 1943 he was the defendant in a public, protracted paternity suit. Denouncing his “leering, sneering attitude” toward the U.S. and his “unsavory” morals, various public officials, citizen groups and gossip columnists led a boycott of his pictures.

J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI put together a dossier on Chaplin that reached almost 2,000 pages. Wrongly identifying him as “Israel Thonstein,” a Jew passing for a gentile, the FBI found no evidence that he had ever belonged to the Communist Party or engaged in treasonous activity. In 1952, however, two days after Chaplin sailed for England to promote Limelight, Attorney General James McGranery revoked his re-entry permit. Loathing the witch-hunts and “moral pomposity” of the cold war U.S., and believing he had “lost the affections” of the American public, Chaplin settled with Oona and their family in Switzerland (where he died in 1977).

With the advent of the ‘60s and the Vietnam War, Chaplin’s American fortunes turned. He orchestrated a festival of his films in New York in 1963. Amid the loudest and longest ovation in its history, he accepted a special Oscar from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1972. There were dissenters. Governor Ronald Reagan, for one, believed the government did the right thing in 1952. During the 1972 visit, Chaplin, at 83, said he’d long ago given up radical politics, a welcome remark in a nation where popular favor has often been synonymous with depoliticization. But the ravishing charm and brilliance of his films are inseparable from his convictions.

At the end of City Lights, when the heroine at last sees the man who has delivered her from blindness, we watch her romantic dreams die. “You?” she asks, incredulous. “Yes,” the Tramp nods, his face, caught in extreme close-up, a map of pride, shame and devotion. It’s the oldest story in show business – the last shall yet be, if not first, at least recognized, and perhaps even loved.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Waiting For Your FeedBack !